The CIA went to extraordinary lengths to cover up the torture program’s futility and brutality, including repeated misrepresentations to senior executive branch officials, Congress and the public.

The Senate intelligence committee’s investigation into the torture program began because the committee discovered that the CIA had videotapes of its interrogations, and that it had destroyed them. Why? According to Jose Rodriguez, chief of the CIA’s counterterrorism center at the time, what was on those tapes was so profoundly disturbing that Rodriguez feared that their public release represented “a threat” to the CIA. Michael Morell, who would eventually become deputy director of the CIA, echoed Rodriguez’s concern in his memoir: “There was no doubt that waterboarding did not make a pretty picture, and publication of those images would have had a devastating effect on CIA, damaged the reputation of the United States abroad, and undermined the security of US officials serving abroad.” Even contract psychologist and torture program architect James Mitchell—who personally waterboarded Abu Zubaydah—says he “had a visceral reaction to the tapes. I thought they were ugly.” He compared them to videos of “aborting babies on YouTube.”

Perhaps this is why the cable authorizing the tapes’ destruction, which was sent by Rodriguez and drafted by his then-chief of staff (and later CIA director) Gina Haspel, specified using an “industrial-strength shredder to do the deed” so as to leave “nothing to chance.” In terms of timing, the CIA’s records make clear that the tapes were destroyed to avoid Congress getting their hands on them:

The tapes’ destruction was only the first of many steps the CIA would take to hide the truth about the torture program, both during and after. Below are just three examples.

The CIA concealed from the president that torture was not working:

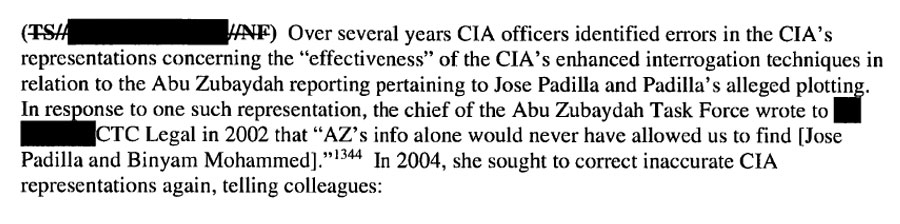

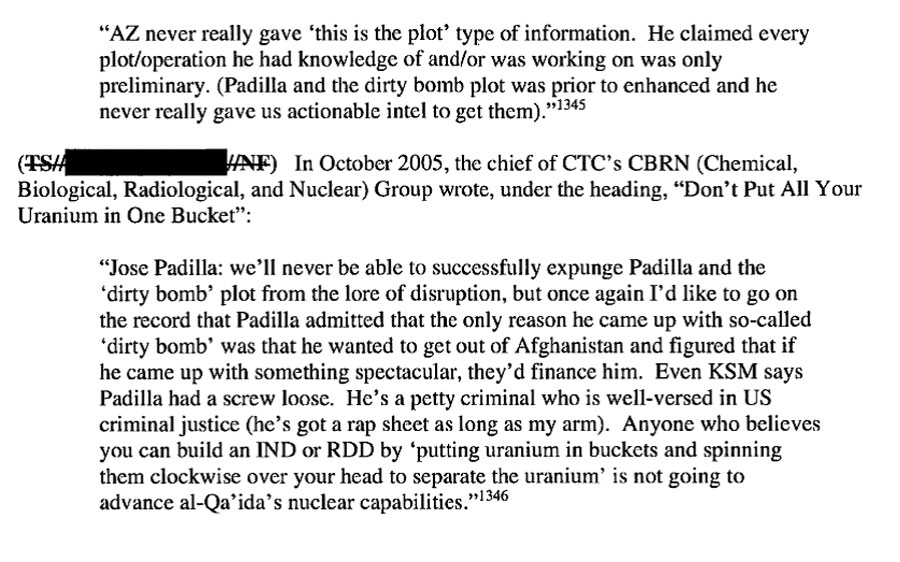

The CIA told the White House, the Department of Justice, Congress and the American public that Abu Zubaydah’s torture produced critical intelligence that thwarted a terrorist plot. And yet, the chief of the Abu Zubaydah task force made clear to colleagues internally that was not the case:

In 2008, the Senate intelligence committee held a hearing on the legal memos relating to the torture program, to which committee members had been provided limited access. The committee sent the CIA written questions following the hearing, including on testimony the witnesses had given regarding torture’s efficacy. The CIA drafted a response that would have finally come clean on its misrepresentations about Abu Zubaydah, but never sent it:

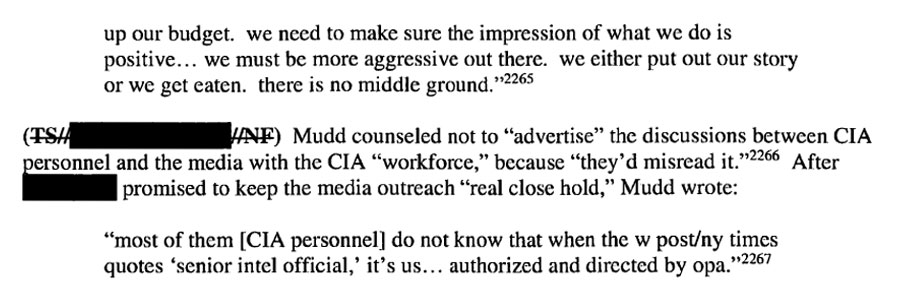

The CIA’s misrepresentations were incorporated into what was essentially a public relations campaign for the media. As the Torture Report’s executive summary finds: “The CIA’s Office of Public Affairs and Senior CIA officials coordinated to share classified information on the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program to select members of the media to counter public criticism, shape public opinion, and avoid congressional action to restrict the CIA’s detention and interrogation authorities and budget.” In 2005, shortly before being interviewed by a media outlet, the deputy director of the CIA’s counterterrorism center wrote the following to a colleague:

Read More

Notifications