Jordan Counseling Group Session Two: Using Our Resources to Help Us Cope

In our international projects, our healing work for torture and war trauma survivors is conducted through group counseling. Groups typically meet for ten weeks. This is the second in a series of posts by Veronica Laveta as she follows the counseling group cycle in Jordan. Veronica Laveta is CVT’s clinical advisor for the Jordan project.

Read the previous entry or the next entry in this series.

—————–

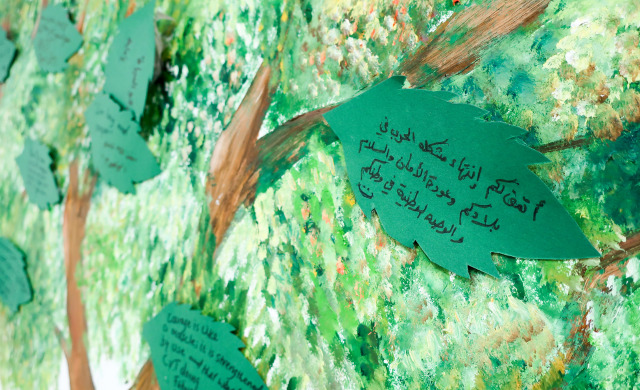

In this session, as we continue to build safety and stability in the group, we aim to draw out survivors’ internal strengths and external resources to counteract the unhelpful tunnel thinking that keeps traumatized people in a state of despair. After reviewing the grounding exercise that helps survivors feel more stable in their bodies and returns them to the present moment, the facilitators use a table metaphor to demonstrate how the more “table legs” one can develop (internal and external resources), the easier it is to carry the burdens on the table. Our innovative counselors built and drew tables to demonstrate this concept (pictured). After one group meeting, counselor Lina noted that survivors “knew they have challenges but they didn’t realize they had so many strengths,” and this sparked a renewed optimism for many of them.

The second exercise introduced the “cognitive triangle” (pictured), a central concept in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) which explores the connection between our thoughts, feelings/physical sensations and behaviors. The group members practiced changing their thoughts to have a positive effect on their feelings and behaviors. Here again, the facilitators engaged in the “art” of counseling, creatively developing visual representations to help the survivors understand the ideas and skills that can help them.

Two groups stood out for me as I watched them unfold throughout the week. In the self-named “Hope” group of older men, facilitators thoughtfully set the tone for empowerment and group support by having each person rotate “hosting” the group. The host hands out name badges, serves people tea and provides tissues. The host this session beamed with pride, appreciating his role. When we reviewed the grounding exercise, one man expressed strong doubts about whether this exercise could really change anything in their lives. But when he practiced it again in the session, he said, with a sheepish smile, “For the first time I felt the current of stress going down my body into the ground. This really made me feel better.” Another said, “I was able to zero out my brain.” I could see doubts start to melt away as they started learning that the more control they have over their thoughts and emotions, the stronger they feel.

One Iraqi man strongly resisted the idea that shifting one’s thoughts could make any difference in his life. He felt very discouraged and talked adamantly about all the difficulties he has had living in Jordan, as well as losing his family in the war and being betrayed by his best friend. “I can’t trust anyone. Even if God sent angels to convince me, I would not believe him,” he said. He recounted that in the past his cynicism and discouragement had been too much for people who were working with him. It was immediately clear this group was not going to give up on him. The facilitators validated the pain of betrayal and the fear of new friendships and also created a safe space for him to express his emotions.

The group members reminded the man he had voted to name their group “Hope.” One group member acknowledged his feelings but nudged him to give space for hope and possibility: “I want to benefit and receive from the group. We are all humans and here to help each other.” Through the course of the group, the man began to relax his shield and started to smile and joke with the others. In our debriefing, the facilitators felt touched by this change in him. Counselor Fatimah remarked, “I was inspired by his smile and that despite his difficult story and discouragement, he could still smile.” Counselor Mohammed had a personal reaction: “When he talked about a friends’ betrayal, I had a flashback to something that had happened to me. I was disconnected for a moment but by me stepping back, it encouraged the group members to be the ‘voice of encouragement.’”

Then there was the “feisty women’s group” as I call them. These older women immediately took to the idea that changing one’s thoughts can change how one feels. It caught on like wildfire. They named the cognitive triangle “the survivor triangle” and immediately were able to come up with thoughts that felt more encouraging to them such as, “Even though I have financial issues, at least I am safe – not like in Syria.” In a role play at the end of the session, they were animatedly shouting out helpful thoughts that could support them: “We have fire in our hearts!” “We are brave.” “It was better that I came here with my daughter so I was able to protect her.”

I was astonished at the dramatic change in some of the women from last session to this one. One woman who had been kidnapped and raped by ISIS had been silent and withdrawn the last group. She sat slightly away from the other members, her body curled in and her eyes downcast. Through this session, I saw her grow stronger and taller with the energy and support of the group, and she claimed her voice, speaking out against the “voice of discouragement.”

The session was very emotional, swinging from one extreme to another. The group members would burst into tears as they touched into their feelings of pain and loss. But then, just as quickly, the mood would change to lightness and laughter after they felt the relief from receiving support and validation. They deeply appreciated learning skills to help them handle their overwhelming emotions. I could see the anxiety in the facilitators when the survivors would break out in sobs, and I certainly felt my own. But then we realized that if we could just be with them and their pain, genuinely validating their suffering while gently opening up other possibilities, big emotions did not have to be a problem. Joy and sadness could co-exist and we could all ride the waves together.

Over time, I have become more comfortable with my role in the groups. Although I am not a facilitator, the participants welcome me warmly and they seem to feel comforted by my presence. As supervisors and advisors, we are seen as additional people who are caring and supporting the process. I’ve been experimenting with how to be a positive presence with my body language, providing smiles of encouragement to help create a safe space.

The feisty women’s group embraced me and Liyam, the psychotherapist trainer supervising the group, with particular vigor. The women commented that they see us as their adopted granddaughters and showered us with kisses and hugs. Their genuine warmth energized me throughout the week.